AI4D blog series: Arabic Speech-to-Moroccan Sign Language Translator: “Learning for Deaf”

Over 5% of the world’s population (466 million people) has disabling hearing loss. 4 million are children [1]. They can be hard of hearing or deaf. Hard of hearing people usually communicate through spoken language and can benefit from assistive devices like cochlear implants. Deaf people mostly have profound hearing loss, which implies very little or no hearing.

The main impact of deaf people is on the individual’s ability to communicate with others in addition to the emotional feelings of loneliness and isolation in society. Consequently, they cannot equally access public services, mostly education and health and have no equal rights in participating in an active and democratic life. This leads to a negative impact in their lives and the lives of the people surrounding them.

Over the world, deaf people use sign language to interact in their community. Hand shapes, lip patterns, and facial expressions are used to express emotions and to deliver meanings. Sign languages are full-fledged natural languages with their own grammar and lexicon. However, they are not universal although they have striking similarities. Sign language can be represented by a form of annotation called Gloss. Each sign is represented by a gloss.

In Morocco, deaf children receive very little education assistance. For many years, they were learning the local variety of sign language from Arabic, French, and American Sign Languages [2]. In April 2019, the government standardized the Moroccan Sign Language (MSL) and initiated programs to support the education of deaf children [3]. However, the involved teachers are mostly hearing, have limited command of MSL and lack resources and tools to teach deaf to learn from written or spoken text. Schools recruit interpreters to help the student understand what is being taught and said in class. Otherwise, teachers use graphics and captioned videos to learn the mappings to signs, but lack tools that translate written or spoken words and concepts into signs.

Around the world, many efforts by different countries have been done to create Machine translations systems from their Language into Sign language. At Laboratoire d’Informatique de Mathématique Appliquée d’Intelligence Artificielle et de Reconnaissance des Formes (LIMIARF https://limiarf.github.io/www/) of Faculty of Sciences of Mohammed V University in Rabat, the Deep Learning Team (DLT) proposed the development of an Arabic Speech-to-MSL translator. The translation could be divided into two big parts, the speech-to-text part and the text-to-MSL part. Our main focus in this current work is to perform Text-to-MSL translation.

This project brings up young researchers, developers and designers. As a team, we conducted many reviews of research papers about language translation to glosses and sign languages in general and for Modern Standard Arabic in particular. We collected data of Moroccan Sign language from governmental, non-governmental sources and form the web. The young researchers also conducted some research on a new way to translate Arabic to a sign gloss. In parallel, young developers was creating the mobile application and the designers designing and rigging the animation avatar. In the following we detail these tasks.

Research reviews

- [4] built a translation system ATLASLang that can generate real-time statements via a signing avatar. The system is a machine translation system from Arabic text to the Arabic sign language. It performs a morpho-syntactic analysis of the text in the input and converts it to a video sequence sentence played by a human avatar. They animate the translated sentence using a database of 200 words in gif format taken from a Moroccan dictionary. If the input sentence exists in the database, they apply the example-based approach (corresponding translation), otherwise the rule-based approach is used by analyzing each word of the given sentence in the aim of generating the corresponding sentence.

- [5] decided to keep the same model above changing the technique used in the generation step. Instead of the rules, they have used a neural network and their proper encoder-decoder model. They analyse the Arabic sentence and extract some characteristics from each word like stem, root, type, gender etc. These features are encapsulated with the word in an object then transformed into a context vector Vc which will be the input to the feed-forward back-propagation neural network. The neural network generates a binary vector, this vector is decoded to produce a target sentence.

- [6] This paper describes a suitable sign translator system that can be used for Arabic hearing impaired and any Arabic Sign Language (ArSL) users as well.The translation tasks were formulated to generate transformational scripts by using bilingual corpus/dictionary (text to sign). They used an architecture with three blocks: First block: recognize the broadcast stream and translate it into a stream of Arabic written script.in which; it further converts such stream into animation by the virtual signer. Therefore, the proposed solution covers the general communication aspects required for a normal conversation between an ArSL user and Arabic speaking non-users. The second block: converts the Arabic script text into a stream of Arabic signs by utilising the rich module of semantic interpretation, language model and supported dictionary of signs. From the language model they use word type, tense, number, and gender in addition to the semantic features for subject, and object will be scripted to the Signer (3D avatar). Third block: works to reduce the semantic descriptors produced by the Arabic text stream into simplified from <Subject, Verb, Object> by helping of ontological signer concept to generalize some terminologies. The proposed tasks employ two phases: training and generative phases. The two phases are supported by the bilingual dictionary/corpus; BC = {(DS, DT)}; and the generative phase produces a set of words (WT) for each source word WS.

- [7] This paper presents DeepASL, a transformative deep learning-based sign language translation technology that enables non-intrusive ASL translation at both word and sentence levels.ASL is a complete and complex language that mainly employs signs made by moving the hands. Each individual sign is characterized by three key sources of information: hand shape, hand movement and relative location of two hands. They use Leap Motion as their sensing modality to capture ASL signs.DeepASL achieves an average 94.5% word-level translation accuracy and an average 8.2% word error rate on translating unseen ASL sentences.

- [8] Achraf and Jemni, introduced a Statistical Sign Language Machine Translation approach from English written text to American Sign Language Gloss. First, a parallel corpus is provided, which is a simple file that contains a pair of sentences in English and ASL gloss annotation. Then a word alignment phase is done using statistical models such as IBM Model 1, 2, 3, improved using a string-matching algorithm for mapping each English word into its corresponding word in ASL Gloss annotation. Then a Statistical Machine translation Decoder is used to determine the best translation with the highest probability using a phrase-based model. Regarding that Arabic deaf community represent 25% from the deaf community around the world, and while the Arabic language is a low-resource language. Many ArSL translation systems were introduced.

- [9] Aouiti and Jemni, proposed a translation system called ArabSTS (Arabic Sign Language Translation System) that aims to translate Arabic text to Arabic Sign Language. This system takes MSA or EGY text as input, then a morphological analysis is conducted using the MADAMIRA tool, next, the output directed to the SVM classifier to determine the correct analysis for each word. Later, the result is written in an XML file and given to an Arabic gloss annotation system. The proposed gloss annotation system provides a global text representation that covers a lot of features (such as grammatical and morphological rules, hand-shape, sign location, facial expression, and movement) to cover the maximum of relevant information for the translation step. This system is based on the Qatari Sign Language rules, each gloss is represented by an Arabic word that identifies one Arabic Sign. Then, The XML file contains all the necessary information to create a final Arab Gloss representation or each word, it is divided into two sections. In the first part, each word is assigned to several fields (id, genre, num, function, indication), and the second part gives the final form of the sentence ready to be translated. By the end of the system, the translated sentence will be animated into Arabic Sign Language by an avatar.

- [10] Luqman and Mahmoud, build a translation system from Arabic text into ArSL based on rules. The proposed work introduces a textual writing system and a gloss system for ArSL transcription. This approach is semantic rule-based. The architecture of the system contains three stages: Morphological analysis, syntactic analysis, and ArSL generation. The Morphological analysis is done by the MADAMIRA tool while the syntactic analysis is performed using the CamelParser tool and the result for this step will be a syntax tree. For generating the ArSL Gloss annotations, the phrases and words of the sentence are lexically transformed into its ArSL equivalents using the ArSL dictionary. After the lexical transformation, the rule transformation is applied. Those rules are built based on differences between Arabic and ArSL, that maps Arabic to ArSL in three levels: word, phrase, and sentence. Then the final representation will be given in the form of ArSL gloss annotation and a sequence of GIF images.

- [11] Automatic speech recognition is the area of research concerning the enablement of machines to accept vocal input from humans and interpreting it with the highest probability of correctness. Arabic is one of the most spoken languages and least highlighted in terms of speech recognition. The Arabic language has three types: classical, modern, and dialectal. Classical Arabic is the language Quran. Modern Standard Arabic (MSA) is based on classical Arabic but with dropping some aspects like diacritics. It is mainly used in modern books, education, and news. Dialectal Arabic has multiple regional forms and is used for daily spoken communication in non-formal settings. With the advent of social media, dialectal Arabic is also written. Those forms of the language result in lexical, morphological and grammatical differences resulting in the hardness of developing one Arabic NLP application to process data from different varieties. Also there are different types of problem recognition but we will focus on continuous speech. Continuous speech recognizers allow the user to speak almost naturally. Due to the utterance boundaries, it uses a special method, which is why it is considered as one of the most difficult systems to create.

- [12] An AASR system was developed with a 1,200-h speech corpus. The authors modeled a different DNN topologies including: Feed-forward, Convolutional, Time-Delay, Recurrent Long Short-Term Memory (LSTM), Highway LSTM (H-LSTM) and Grid LSTM (GLSTM). The best performance was from a combination of the top two hypotheses from the sequence trained GLSTM models with 18.3% WER.

- [13] A comparison for some of the state-of-the-art speech recognition techniques was shown. The authors applied those techniques only to a limited Arabic broadcast news dataset. The different approaches were all trained with a 50-h of transcription audio from a news channel “Al-jazirah”. The best performance obtained was the hybrid DNN/HMM approach with the MPE (Minimum Phone Error) criterion used in training the DNN sequentially, and achieved 25.78% WER.

- [14] Speech recognition using deep-learning is a huge task that its success depends on the availability of a large repository of a training dataset. The availability of open-source deep-learning enabled frameworks and Application Programming Interfaces (API) would boost the development and research of AASR. There are multiple services and frameworks that provide developers with powerful deep-learning abilities for speech recognition. One of the marked applications is Cloud Speech-to-Text service from Google which uses a deep-learning neural network algorithm to convert Arabic speech or audio file to text. Cloud Speech-to-Text service allows for its translator system to directly accept the spoken word to be converted to text then translated. The service offers an API for developers with multiple recognition features.

- [15] Another service is Microsoft Speech API from Microsoft. This service helps developers to create speech recognition systems using deep neural networks. IBM cloud provides Watson service API for speech to text recognition support modern standard Arabic language.

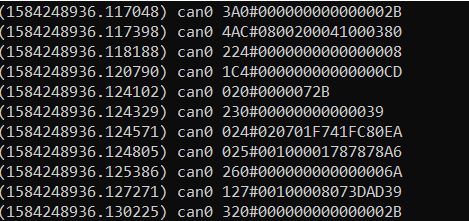

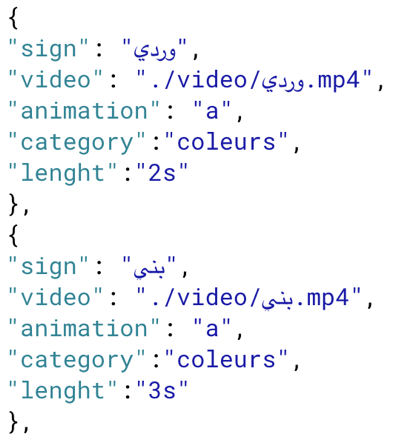

Data collection

Because of the lack of data resources about the Arabic sign language. We dedicated a lot of energy to collect our own datasets. For this end, we relied on the available data from some official [16] and non-official sources [17, 18, 19] and collected, until now, more than 100 signs. The dataset is composed of videos and a .json file describing some meta data of the video and the corresponding word such as the category and the length of the video.

Published Research

Our long abstract paper [20] intitled ‘Towards A Sign Language Gloss Representation Of Modern Standard Arabic’ was accepted for presentation at the Africa NLP workshop of the 8th International Conference on Learning Representations (ICLR 2020) in April 26th in Addis Ababa Ethiopia. In this paper we were interested in the first stage of the translation from Modern Standard Arabic to sign language animation that is generating a sign gloss representation. We identified a set of rules mandatory for the sign language animation stage and performed the generation taking into account the pre-processing proven to have significant effects on the translation systems. The presented results are promising but far from well satisfying all the mandatory rules.

Mobile Application

The application is developed with Ionic framework which is a free and open source mobile UI toolkit for developing cross-platform apps for native iOS, Android, and the web : all from a single codebase. The application is composed of three main modules: the speech to text module, the text to gloss module and finally the gloss to sign animation module.

In the speech–to–text module, the user can choose between the Modern Standard Arabic language and the French language. The user can long-press on the microphone and speak or type a text message. The voice message will be transcribed to a text message using the google cloud API services. In the text-to-gloss module, the transcribed or typed text message is transcribed to a gloss. This module is not implemented yet. The results from our published paper are currently under test to be adopted. Finally, in the the gloss–to-sign animation module, at first attempts, we tried to use existing avatars like ‘Vincent character’ [ref], a popular avatar with high-quality rigged character freely available on Blender Cloud. We started to animate Vincent character using Blender before we figured out that the size of generated animation is very large due to the character’s high resolution. Therefore, in order to be able to animate the character with our mobile application, 3D designers joined our team and created a small size avatar named ‘Samia’. The designers recommend using Autodesk 3ds Max instead of Blender initially adopted. 3ds Max is designed on a modular architecture, compatible with multiple plugins and scripts written in a proprietary Maxscript language. In future work, we will animate ‘Samia’ using Unity Engine compatible with our Mobile App.

References

- [1] World Health Organization website: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/deafness-and-hearing-loss

- [2] Ethnologue website: https://www.ethnologue.com/language/xms

- [3] Moroccan governement website: http://www.maroc.ma/fr/actualites/mme-hakkaouila-standardisation-de-la-langue-des-signes-un-pas-vers-lintegration-sociale

- [4] Brour, Mourad & Benabbou, Abderrahim. (2019). ATLASLang MTS 1: Arabic Text Language into Arabic Sign Language Machine Translation System. Procedia Computer Science. 148. 236-245. 10.1016/j.procs.2019.01.066.

- [5] Brour, Mourad & Benabbou, Abderrahim. (2019). ATLASLang NMT: Arabic text language into Arabic sign language neural machine translation. Journal of King Saud University – Computer and Information Sciences. 10.1016/j.jksuci.2019.07.006.

- [6] Biyi Fang, Jillian Co, Mi Zhang. (2018). ”DeepASL: Enabling Ubiquitous and Non-Intrusive Word and Sentence-Level Sign Language Translation”. 15th ACM Conference on Embedded Network Sensor Systems.https://doi.org/10.1145/3131672.3131693

- [7] Omar H. Al-Barahamtoshy, Hassanin M. Al-Barhamtoshy. (2017). ”Arabic Text-to-Sign (ArTTS) Model from Automatic SR System”. 3rd International Conference on Arabic Computational Linguistics, ACLing 2017, Dubai, United Arab Emirates. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2017.10.122

- [8] A. Othman and M. Jemni, “Statistical Sign Language Machine Translation: from English written text to American Sign Language Gloss,” vol. 8, no. 5, p. 9, 2011.

- [9] N. Aouiti and M. Jemni, “Translation System from Arabic Text to Arabic Sign Language,” JAIS, vol. 3, no. 2, pp. 57–70, Dec. 2018, doi:33633/jais.v3i2.2041.

- [10] H. Luqman and S. A. Mahmoud, “Automatic translation of Arabic text-to-Arabic sign language,” Universal Access in the Information Society, vol. 18, pp. 939–951, 2018, doi:1007/s10209-018-0622-8.

- [11] Algihab, W., Alawwad, N., Aldawish, A., & AlHumoud, S. (2019). Arabic Speech Recognition with Deep Learning: A Review. Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 15–31. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-21902-4_2

- [12] AlHanai, T., Hsu, W.-N., Glass, J.: Development of the MIT ASR system for the 2016 Arabic multi-genre broadcast challenge. In: 2016 IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT), San Diego, CA, pp. 299–304 (2016)

- [13] Cardinal, P., et al.: Recent advances in ASR applied to an Arabic transcription system for AlJazeera, p. 5.

- [14] Khurana, S., Ali, A.: QCRI advanced transcription system (QATS) for the Arabic multidialect broadcast media recognition: MGB-2 challenge. In: 2016 IEEE Spoken Language Technology Workshop (SLT), San Diego, CA, pp. 292–298 (2016)

- [15] Graciarena, M., Kajarekar, S., Stolcke, A., Shriberg, E.: Noise robust speaker identification for spontaneous Arabic speech. In: 2007 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing, ICASSP 2007, Honolulu, HI, pp. IV-245–IV-248 (2007)

- [16] http://www.social.gov.ma/fr/accueil

- [17] https://www.handspeak.com/word/search/index.php?id=7508

- [18] https://www.ifes.org/sites/default/files/electoral-lexicon-manual-in-moroccan-sign-language.pdf

- [19] https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC-KdJajipGWAYrrQZ8NHl7g

- [20]- https://arxiv.org/login?next_page=/submit/3105331/view

Reposted within the project “Network of Excellence in Artificial Intelligence for Development (AI4D) in sub-Saharan Africa” #UnitedNations #artificialintelligence #SDG #UNESCO #videolectures #AI4DNetwork #AI4Dev #AI4D